Cracking a GovCon Code: Understanding DoD OTAs

May 27, 2025

Reading Time: 5 minutes

Navigating the complexities of government contracting often means working within the confines of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR). However, another avenue that has gained more attention in recent months is Other Transaction Agreements (OTAs). (Note: Try not to confuse OTA with Other Transaction Authority, which is the agency that actually issues the agreements.)

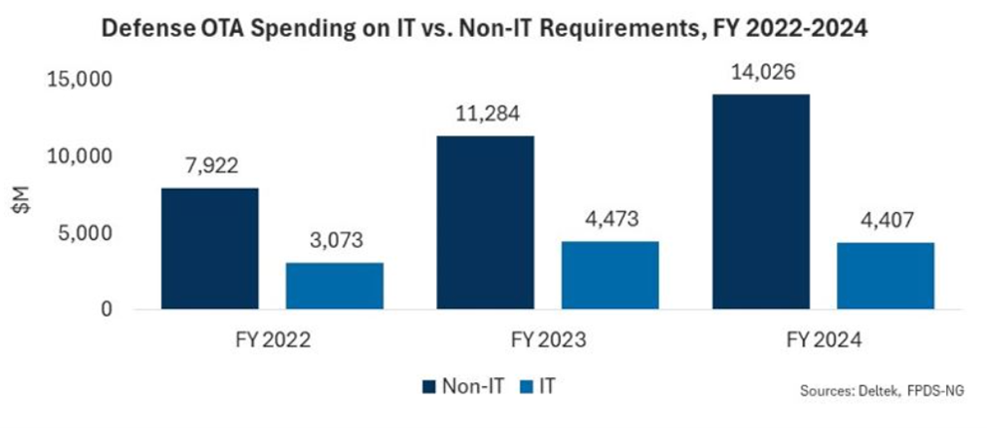

This less-traditional method of procurement isn’t new, just newly popular. According to a GovWin market analysis, it’s estimated that billions of dollars are awarded via OTAs annually. This post will explore the ins and outs of OTAs and why they’re becoming a go-to choice for certain agencies and industry players alike.

Defense OTA spending on IT vs. Non-IT requirements. Numbers in the millions. (Source: Deltek)

Why are OTAs relevant?

Since the Trump Administration took office in January, there has been a heavy emphasis on using OTAs more often because the current software acquisition process is “slow and bureaucratic". As such, there’s been a flurry of directives released to reshape the defense acquisition process.

|

Date of Release |

Title |

Key Takeaways |

|

March 6, 2025 |

Memorandum from the Secretary of Defense: Directing Modern Software Acquisition to Maximize Lethality |

|

|

April 9, 2025 |

Executive Order: Modernizing Defense Acquisitions and Spurring Innovation in the Defense Industrial Base |

|

|

April 15, 2025 |

Executive Order: Restoring Common Sense to Federal Procurement |

|

|

April 16, 2025 |

Executive Order: Enforcing Cost Effective Commercial Solutions |

|

What are OTAs?

OTAs are agreements between certain federal agencies and non-traditional government contractors primarily used for research and development (R&D) efforts. However, not all agencies have the authority to use OTAs (read this article from GAO to learn more about OTA usage).

There are three types of OTAs:

1. Research: Research OTAs support basic, applied, and advanced research, encouraging dual-use R&D while minimizing government regulatory burdens on companies. The Office Under the Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering provides policy and guidance on Research OTAs.

2. Prototype: Prototype OTAs acquire prototype capabilities for dual-use and defense-specific projects. Successful prototypes can transition into production without additional competition, simplifying the path to follow-on production.

3. Production: Production OTAs follow successful prototype OTAs, allowing the government to move directly into production with further competition, streamlining the process for transitioning to full-scale production.

Here are some fun facts about OTAs:

- OTAs are considered legally valid contracts, just not procurement contracts. They’re comprised of the elements that make up contracts: offer, acceptance, consideration, authority, legal purpose, and meeting of the minds.

- There’s no FAR compliance required! OTAs are governed by the United States Code (USC). The main difference between the FAR and USC is that federal agencies created the FAR, and Congress created the USC. What this means is that there is usually more flexibility in the USC than in the FAR.

- OTAs streamline procurement for non-traditional defense contractors (NTDCs), startups, and commercial businesses. An NTDC is any company that isn’t heavily involved in contracts with the DoD or they’re not fully covered under Cost Accounting Standards (CAS). This means they are often new to the defense market or have minimal experience working with the government.

- There are avenues for traditional government contractors to use OTAs; however, they need to partner with an NTDC that contributes a meaningful share of the work. Note that “meaningful share” refers to a situation where the traditional government contractor and NTDC agree to share the cost and risk of a project.

- You can enter an OTA through various types of solicitation: CSOs, Request for Prototypes (RPPs), white papers, Broad Agency Announcements (BAAs), and Research Opportunity Announcements (ROAs). See this ROA from the National Institutes of Health as an example.

- Awards are given directly or through consortia.

Consortia – what’s that?

Consortia (plural for consortium) is a group of traditional and non-traditional organizations that collaborate under an OTA to develop solutions like prototypes, technologies, or services for government needs. Federal agencies may work directly with a consortium or through a consortium management firm to coordinate complex, multi-specialty OTAs (here’s a list of consortia from Deltek). A consortium aims to help government buyers access emerging technologies and assist non-traditional contractors with federal processes. In some cases, a consortium is the liaison between a NTDC and the government – they handle the agreement’s administrative requirements, allowing the NTDC to focus on developing and delivering the technology. Think: if you don’t currently contract with the government, partnering with traditional contractors could set you up for success.

The size of a consortium can range from a couple of members to 1,000+. It may cost $500-$1,000 to be a member, but the benefits usually outweigh this disadvantage: the consortium exists to drive faster innovation through collaboration, accelerate the award process (since competition is already completed), and pre-position members to meet emerging technology needs.

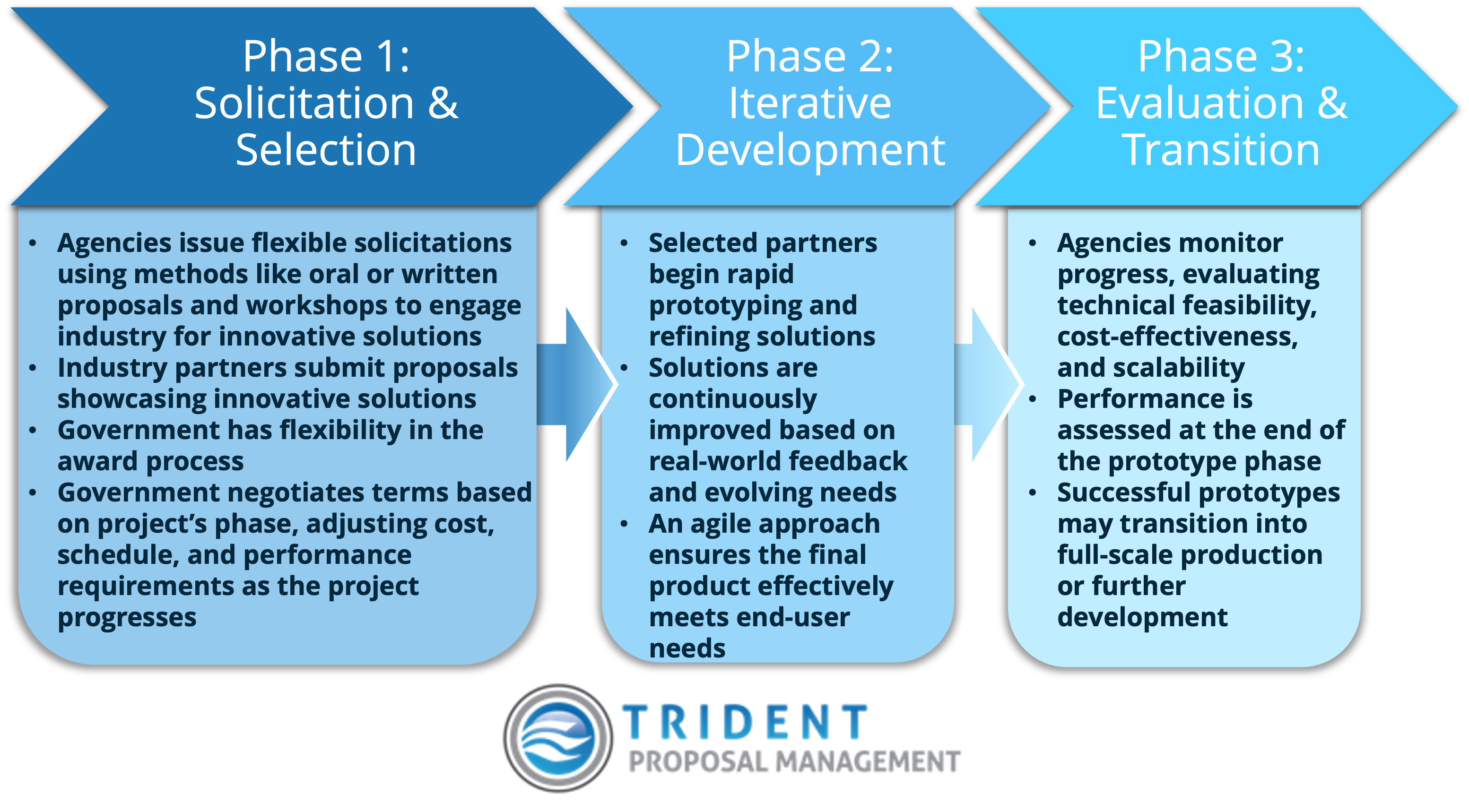

What is the OTA process?

Now that we’ve discussed the complexities of OTAs, here’s what the process looks like:

What are the pros and cons of OTAs?

OTAs sound like a winning approach. However, we’d be remiss if we didn’t point out the pros and cons of pursuing an OTA.

Pros

- Offers more flexibility – customizable terms and conditions.

- Innovation-focused – prioritizes disruption over past performance. To put it another way, you don’t need to have a minimum number of existing contracts to qualify, whereas past performance is often an evaluated area on a standard solicitation.

- Speeds up innovation by enabling rapid acquisition of cutting-edge technology.

- The award process can sometimes be faster than standard procurements (30–90-day evaluations vice an evaluation timeline that significantly varies).

Cons

- The performing vendor has to determine the project schedule, success metrics, milestones, and outcomes. The government doesn’t specify contract requirements and terms and conditions in a typical Statement of Work (SOW) or Performance Work Statement (PWS).

- OTAs don’t follow typical acquisition regulations (e.g., FAR, Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement [DFARS], CAS). These regulations protect against waste, fraud, abuse, and corruption, and provide mechanisms for ensuring fair and reasonable pricing and government ownership of IP.

- Businesses need to be well-versed in the terms of their OTA to understand what IP they own and what IP they’re surrendering to the government.

- If your technology isn’t applicable or if the use case is limited, there’s no guarantee of follow-on work (as opposed to a 5-year PoP on a services-based contract).

Overview

OTAs are a unique procurement method used by several federal agencies (especially the DoD) to acquire research, prototypes, or production capabilities outside the FAR. They’re not FAR-based contracts – OTAs are in a league of their own! They provide flexibility and foster innovation to NTDCs and traditional government contractors.

We hope this exploration into OTAs broadens your understanding of what they are and why they’re important. Contact Trident today and let us help you with your next OTA bid.

Looking for More?

We have several blogs that touch on a similar topic. Check out these blogs below:

- Essential Contracting Advice for Small Businesses from the Navy Contracting Summit

- Beyond the Horizon: Key Takeaways from the 2024 Navy Contracting Summit

- Funding Opportunities in DoD's Small Business Innovation Research: What You Need to Know

- Non-Traditional Avenues for Small Businesses

Written by Jen Concannon

Jen is a capture and proposal manager at Trident. Her skills include proposal support, technical editing, and formatting. She is also a licensed program management professional (PMP). As a military spouse based on the East Coast, she supports clients around the world as part of our globally dispersed team.